Medieval Period is defined as the period in Europe between the fall of the Roman Empire and the start of the Renaissance. It is divided into three (3) ages . Namely as : The Early Middle ages , The High Middle ages and The Later Middle ages. This three (3) named ages completes the whole nine hundred (900) years of the MEDIEVAL PERIOD . THE EARLY MIDDLE is an age wherein many people suffers from right and left wars , this period do not have any peace and harmony at all and that's why this age is called "DARK AGES".... The next part of the Medieval period is what we called THE HIGH MIDDLE AGES , this happened between 11-13 century. During this time the Feudalism System was lifted up and the agriculture and economy was developed once again . CITY-STATE also arose during this times. The last but not the least is the LATER MIDDLE AGES - this is the time wherein the feudalism system , the peasantry and other things included in the feudalism system was bared down . This was the period wherein the people suffers from food shortening and another left and right wars ... And now .. Lets tackle the life of the medieval people during medieval ages...

Daily life during the Middle Ages is sometimes hard to fathom. Pop culture loves to focus on exciting medieval moments-heroic knights charging into battle; romantic liaisons between royalty and commoner; breakthroughs and discoveries made. But life for your average person during the Dark Ages was very routine, and activities revolved around an agrarian calendar.

Most of the time was spent working the land, and trying to grow enough food to survive another year. Church feasts marked sowing and reaping days, and occasions when peasant and lord could rest from their labors.

Social activities were important, and every citizen in a medieval town would be expected to attend. Fairs with troubadours and acrobats performing in the streets…merchants selling goods in the town square…games of chance held at the local tavern…tournaments featuring knights from near and abroad…these were just some of the ways medieval peasants spent their leisure time. Medieval weddings were cause for the entire town to celebrate.

Social activities were important, and every citizen in a medieval town would be expected to attend. Fairs with troubadours and acrobats performing in the streets…merchants selling goods in the town square…games of chance held at the local tavern…tournaments featuring knights from near and abroad…these were just some of the ways medieval peasants spent their leisure time. Medieval weddings were cause for the entire town to celebrate.  Medieval superstitions held sway over science, but traveling merchants and returning crusaders told of cultures in Asia, the Middle East and Africa that had advanced learning of the earth and the human body. Middle Age food found new flavor courtesy of rare spices that were imported from the East. Schools and universities were forming across Western Europe that would help medieval society evolve from the Dark Ages on its way to a Renaissance of art and learning.

Medieval superstitions held sway over science, but traveling merchants and returning crusaders told of cultures in Asia, the Middle East and Africa that had advanced learning of the earth and the human body. Middle Age food found new flavor courtesy of rare spices that were imported from the East. Schools and universities were forming across Western Europe that would help medieval society evolve from the Dark Ages on its way to a Renaissance of art and learning. The middle ages (5th – 15th Centuries AD), often termed The Dark Ages, were actually a time of great discovery and invention. The Middle ages also saw major advances in technologies that already existed, and the adoption of many Eastern technologies in the West. This is a list of the ten greatest inventions of the Middle Ages (excluding military inventions).

1. The Heavy Plough 5th Century AD

In the basic mouldboard plough the depth of the cut is adjusted by lifting against the runner in the furrow, which limited the weight of the plough to what the ploughman could easily lift. These ploughs were fairly fragile, and were unsuitable for breaking up the heavier soils of northern Europe. The introduction of wheels to replace the runner allowed the weight of the plough to increase, and in turn allowed the use of a much larger mouldboard that was faced with metal. These heavy ploughs led to greater food production and eventually a significant population increase around 600 AD.

2. Tidal Mills 7th Century AD

A tide mill is a specialist type of water mill driven by tidal rise and fall. A dam with a sluice is created across a suitable tidal inlet, or a section of river estuary is made into a reservoir. As the tide comes in, it enters the mill pond through a one way gate, and this gate closes automatically when the tide begins to fall. When the tide is low enough, the stored water can be released to turn a water wheel. The earliest excavated tide mill, dating from 787, is the Nendrum Monastery mill on an island in Strangford Lough in Northern Ireland. Its millstones are 830mm in diameter and the horizontal wheel is estimated to have developed 7/8HP at its peak. Remains of an earlier mill dated at 619 were also found.

3. The Hourglass 9th Century AD

Since the hourglass was one of the few reliable methods of measuring time at sea, it has been speculated that it was in use as far back as the 11th century, where it would have complemented the magnetic compass as an aid to navigation. However, it is not until the 14th century that evidence of their existence was found, appearing in a painting by Ambrogio Lorenzetti 1328. The earliest written records come from the same period and appear in lists of ships stores. From the 15th century onwards they were being used in a wide range of applications at sea, in the church, in industry and in cookery. They were the first dependable, reusable and reasonably accurate measure of time. During the voyage of Ferdinand Magellan around the globe, his vessels kept 18 hourglasses per ship. It was the job of a ship’s page to turn the hourglasses and thus provide the times for the ship’s log. Noon was the reference time for navigation, which did not depend on the glass, as the sun would be at its zenith.

4. Blast Furnace 12th Century AD

The oldest known blast furnaces in the West were built in Dürstel in Switzerland, the Märkische Sauerland in Germany, and Sweden at Lapphyttan where the complex was active between 1150 and 1350. At Noraskog in the Swedish county of Järnboås there have also been found traces of blast furnaces dated even earlier, possibly to around 1100. Knowledge of certain technological advances was transmitted as a result of the General Chapter of the Cistercian monks, including the blast furnace, as the Cistercians are known to have been skilled metallurgists. According to Jean Gimpel, their high level of industrial technology facilitated the diffusion of new techniques: “Every monastery had a model factory, often as large as the church and only several feet away, and waterpower drove the machinery of the various industries located on its floor.” Iron ore deposits were often donated to the monks along with forges to extract the iron, and within time surpluses were being offered for sale. The Cistercians became the leading iron producers in Champagne, France, from the mid-13th century to the 17th century, also using the phosphate-rich slag from their furnaces as an agricultural fertilizer.

The oldest known blast furnaces in the West were built in Dürstel in Switzerland, the Märkische Sauerland in Germany, and Sweden at Lapphyttan where the complex was active between 1150 and 1350. At Noraskog in the Swedish county of Järnboås there have also been found traces of blast furnaces dated even earlier, possibly to around 1100. Knowledge of certain technological advances was transmitted as a result of the General Chapter of the Cistercian monks, including the blast furnace, as the Cistercians are known to have been skilled metallurgists. According to Jean Gimpel, their high level of industrial technology facilitated the diffusion of new techniques: “Every monastery had a model factory, often as large as the church and only several feet away, and waterpower drove the machinery of the various industries located on its floor.” Iron ore deposits were often donated to the monks along with forges to extract the iron, and within time surpluses were being offered for sale. The Cistercians became the leading iron producers in Champagne, France, from the mid-13th century to the 17th century, also using the phosphate-rich slag from their furnaces as an agricultural fertilizer.5. Liquor 12th Century AD

The first evidence of true distillation comes from Babylonia and dates from the fourth millennium BC. Specially shaped clay pots were used to extract small amounts of distilled alcohol through natural cooling for use in perfumes, however it is unlikely this device ever played a meaningful role in the history of the development of the still. Freeze distillation, the “Mongolian still”, are known to have been in use in Central Asia as early as the 7th century AD. The first method involves freezing the alcoholic beverage and removing water crystals. The development of the still with cooled collector—necessary for the efficient distillation of spirits without freezing—was an invention of Muslim alchemists in the 8th or 9th centuries. In particular, Geber (Jabir Ibn Hayyan, 721–815) invented the alembic still; he observed that heated wine from this still released a flammable vapor, which he described as “of little use, but of great importance to science”

The first evidence of true distillation comes from Babylonia and dates from the fourth millennium BC. Specially shaped clay pots were used to extract small amounts of distilled alcohol through natural cooling for use in perfumes, however it is unlikely this device ever played a meaningful role in the history of the development of the still. Freeze distillation, the “Mongolian still”, are known to have been in use in Central Asia as early as the 7th century AD. The first method involves freezing the alcoholic beverage and removing water crystals. The development of the still with cooled collector—necessary for the efficient distillation of spirits without freezing—was an invention of Muslim alchemists in the 8th or 9th centuries. In particular, Geber (Jabir Ibn Hayyan, 721–815) invented the alembic still; he observed that heated wine from this still released a flammable vapor, which he described as “of little use, but of great importance to science” Medieval villages consisted of a population comprised of mostly of farmers. Houses, barns sheds, and animal pens clustered around the center of the village, which was surrounded by plowed fields and pastures. Medieval society depended on the village for protection and a majority of people during these centuries called a village home. Most were born, toiled, married, had children and later died within the village, rarely venturing beyond its boundaries.

Medieval villages consisted of a population comprised of mostly of farmers. Houses, barns sheds, and animal pens clustered around the center of the village, which was surrounded by plowed fields and pastures. Medieval society depended on the village for protection and a majority of people during these centuries called a village home. Most were born, toiled, married, had children and later died within the village, rarely venturing beyond its boundaries.  Common enterprise was the key to a village's survival. Some villages were temporary, and the society would move on if the land proved infertile or weather made life too difficult. Other villages continued to exist for centuries. Every village had a lord, even if he didn't make it his permanent residence, and after the 1100's castles often dominated the village landscape. Medieval Europeans may have been unclear of their country's boundaries, but they knew every stone, tree, road and stream of their village. Neighboring villages would parley to set boundaries that would be set out in village charters.

Common enterprise was the key to a village's survival. Some villages were temporary, and the society would move on if the land proved infertile or weather made life too difficult. Other villages continued to exist for centuries. Every village had a lord, even if he didn't make it his permanent residence, and after the 1100's castles often dominated the village landscape. Medieval Europeans may have been unclear of their country's boundaries, but they knew every stone, tree, road and stream of their village. Neighboring villages would parley to set boundaries that would be set out in village charters. Village life would change from outside influences with market pressures and new landlords. As the centuries passed, more and more found themselves drawn to larger cities. Yet modern Europe owes much to these early medieval villages.

|

| MEDIEVAL LANDLORD |

|

| Peasants |

Village life would change from outside influences with market pressures and new landlords. As the centuries passed, more and more found themselves drawn to larger cities. Yet modern Europe owes much to these early medieval villages.

|

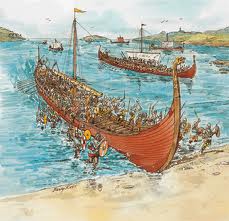

| THE INVADERS |

Viking invasions were a major factor in the development of cities during the early Middle Ages. These invaders often plundered more than they could carry, sold surplus goods to surrounding villages and created base camps to be used for trading. Dublin, Ireland's roots began as a Viking base camp. To protect themselves, villages began erecting walls and fortifying their positions. This lead to the great medieval walled cities that can still be seen in modern Europe.

These walled cities became known as "bourgs," "burghs," and later, bouroughs. Inhabitants were known as bourgeois. By the mid-900s, these fortified towns dotted the European landscape from the Mediterranean as far north as Hamburg, Germany.

|

| VIKINGS |

Comfort was not always easy to find, even in the wealthiest of households. Heating was always a problem with stone floors, ceiling and walls. Little light came in from narrow windows, and oil and fat-based candles often produced a pungent aroma. Furniture consisted of wooden benches, long tables, cupboards and pantries. Linen, when afforded, might be glued or nailed to benches to provide some comfort. Beds, though made of the softest materials, were often rife with bedbugs, lice and other biting insects. Some tried to counter this by taucking in sheets at nighttime in hopes of smothering the pests, while others rubbed oily liniments on their skin before retiring.

THE END .....